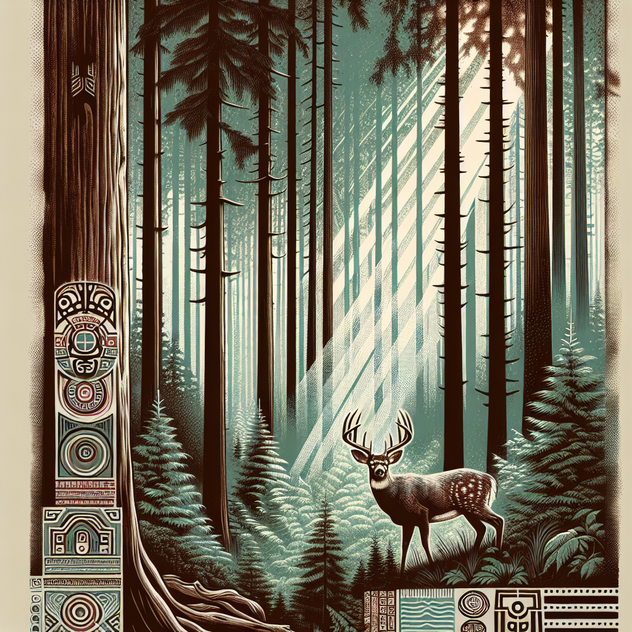

Deep in the forests of eastern Washington, an unsettling discovery has stirred concern among wildlife officials and Indigenous communities alike. A case of chronic wasting disease (CWD) was confirmed in a white-tailed deer on the Spokane Indian Reservation — marking a troubling moment for both the natural ecosystem and the cultural practices that depend on it. The disease, which affects deer, elk, and moose by progressively damaging their brains and nervous systems, has no known cure and is invariably fatal.

CWD isn’t new to the United States, but its arrival in new regions always raises alarms. It’s especially concerning for communities like the Spokane Tribe, where hunting is not only a source of sustenance but also a deeply embedded tradition. This detection doesn’t just signal a health issue in deer populations — it threatens to disrupt seasonal practices, economic stability, and ancestral heritage tied closely to the land and its creatures.

What makes chronic wasting disease so dangerous is its stealthy nature. Infected animals can carry and spread the illness long before visible symptoms appear, quietly contaminating the environment. The prions responsible for the disease can linger in soil and plants for years, making eradication a nearly impossible task once an outbreak begins. This creates a complex challenge for wildlife managers, who must act swiftly yet carefully to mitigate its spread.

This situation offers a moment of reflection about the broader implications of disease management in wildlife. Balancing scientific strategy with Indigenous knowledge systems could be key in addressing this crisis effectively. Tribal communities often possess generations of ecological understanding that, when integrated with modern research, could lead to more culturally respectful and sustainable interventions moving forward.

The detection of CWD on the Spokane Reservation is more than just a health alert—it’s a symbolic reminder of the delicate balance between human practices and environmental health. As officials and tribal leaders navigate the next steps, one can only hope that cooperation, respect for tradition, and rigorous science will unite to face this invisible adversary in the wild.